Franz Kafka

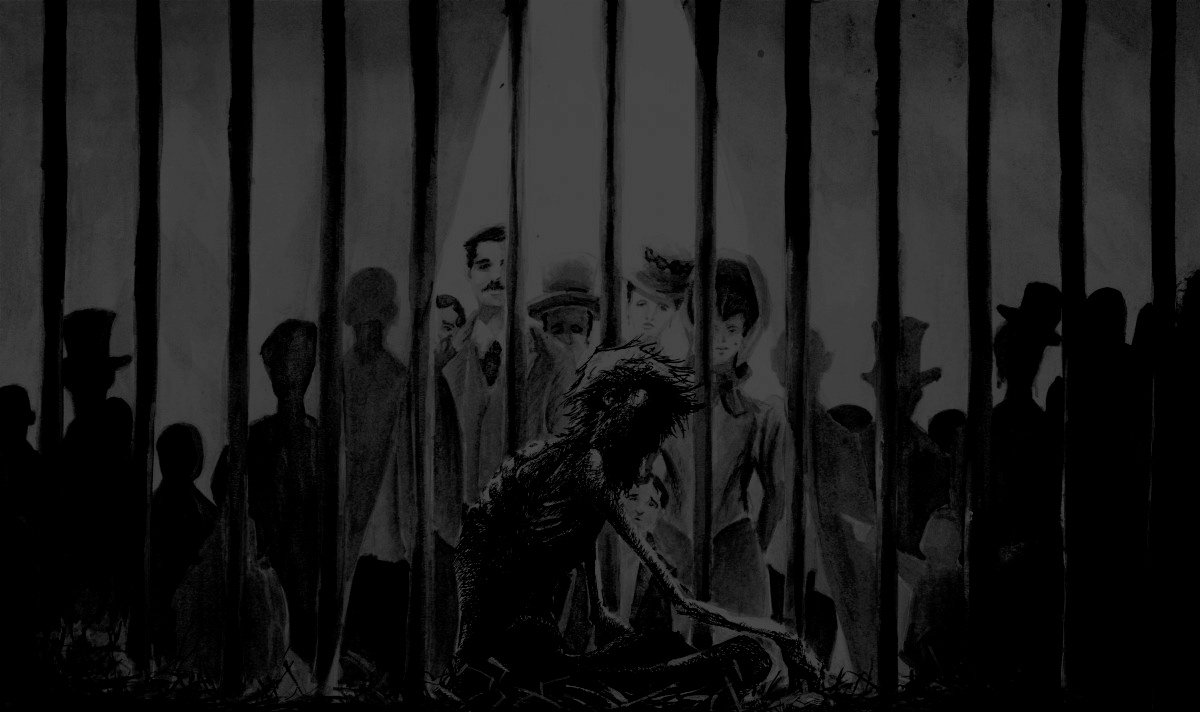

An artist whose art is starvation. A salesman who transforms into a beetle. A clerk accused of an unknown crime. What does it mean for something to be ‘Kafkaesque’ and who was the man behind the vision?

Here are two short stories which attempt to but fall short of exploring the great Franz Kafka.

'Letter to His Father' is a posthumously published work of Franz Kafka, a letter he had written and addressed to his estranged father, Hermann Kafka, a controlling and ill-tempered shopkeeper who expressed violent disapproval of his son. Franz Kafka often wrote fiction depicting authoritarian bureaucracies of arbitrary power and needlessly complex philosophy, but within these fantastical systems, there is the haunting presence of Hermann Kafka. The letter Franz Kafka wrote was over a hundred pages, detailing a retrospective journey of their relationship in which Franz Kafka unleashes his frustration, accuses his father, confesses his guilt, seeks reconciliation, and asks for forgiveness. Ultimately, the letter was never delivered.

The Letter

Dearest Father,

You asked me recently why I maintain that I am afraid of you. As usual, I was unable to think of any answer to your question, partly for the very reason that I am afraid of you…

***

At thirty-six years of age, Franz Kafka knew that death was near. As he looked into the mirror, he was somewhat repulsed by the sickly creature that stood before him. Upon its frail body, a worn face stared blankly back at him with ebony eyes, one of which was ever so slightly misaligned. As Franz ran his fingers through tufts of hair, the creature mimicked his actions, revealing dense slivers of grey emerging from its temple. Its spine protruded from its back and there were defined contours between each of its ribs like that of a stray dog in the street.

It was a cold morning and the two hastily detached their gaze from one another as a breath of winter crept through the bedroom window. Franz shuffled towards the source of discomfort, clutching his scrawny abdomen before forcing the window shut.

It was late when Franz was awoken by a horrifying vision. He had dreamt of monsters and men. Giant beasts with the horns of a ram and the fangs of a lion reigned an endless terror upon the world. Their eyes were desolate like shadows and they could crush a man in their palm.

Franz was a helpless man, running for his life amongst a city’s rubble, attempting to escape the monsters’ relentless pursuit. Superior in stride, they verged upon their prey. However, just before their colossal feet could crush him from existence, reality saved him.

He was a boy of ten who was safely nested beneath his blanket and the world around him was not under the dominion of terrifying creatures. Nevertheless, Franz was still mortified by the ordeal. The unfamiliar and eerie sounds of evening life could be heard from outside, and the whistles of wind seeped into his room like ghostly spirits. He hid beneath the bedsheets where he could feel the warmth of his own rapid breaths.

“Father!” he cried out. Franz paused for a moment. He sat up with his arms wrapped around his legs, thinking of an excuse to demand his father’s attention. “I would like some water please,” he continued. No reply came but Franz knew that his father had heard him. The dull pounding of footsteps commenced, slow and muted at first, gradually crescendoing and accelerating into a menacing stride. Franz now regretted his choice of action, but it was too late. His bedroom door flung open and, in the frame, stood the ominous silhouette of his father, wielding a candle in one hand and fingers clenched in the other.

The small boy trembled at the sight of the figure whose shoulders were broad like a bull and limbs stout like a ram. With great agility and aggression, it marched towards the bed, yanking the small boy by the ear and hauling him out of the room. As the boy flailed, the man’s grip grew stronger.

By the time they reached the stairs, Franz’s ear was throbbing, and he had no choice but to follow his father. He was dragged towards the balcony where his father lay down the candle and opened the door to the outside. A gale of cold piercing wind collided with them, extinguishing the nearby flame. His father let go of his ear but only to grab Franz by the shoulders, thrusting him into the dark winter night.

As his face crashed into the rough snow on the ground, Franz heard the door slam behind him followed by the click of a lock. Abandoned like a dog.

Still quivering, Franz dressed hastily. He hated winter. The empty streets of Austria had been buried beneath a thick blanket of white. In the distance, he could hear the steam train and the roars of its industrial lungs slowly fading into the distance. The usual commotion of passing cyclists and pedestrians were instead replaced by the hissing of wind and the susurration of falling snow. The city had retreated to the warmth and shelter of their homes.

Glad that he was not on the other side of the window, Franz manoeuvred to his desk where a great chaos was laid before him. He did not know how many pages he had written, but it was enough so that the wooden surface of the desk was not visible. At a glance they were merely scribbles, untidy and free, but veiled within his inky words was a voice, struggling to be heard. Franz gathered the pages, rotating the edges so that they formed a neat stack. He had promised himself that today would be the day that he delivered this letter.

Within his hand Franz held the axe for the frozen sea within him, but in letting the blade fall, he felt as though he would cut away a piece of himself in the process. The letter was a testimony to his father’s persistent abuse, but it was also an admission of guilt as a pathetic and deplorable son. For years, the persistent trauma of his childhood had tormented him, and it would continue to do so unless he could deliver this letter. With the end in sight, this neglected crisis had finally resurfaced, and Franz was now forced to make a decision. Logic may indeed be unshakeable, but it cannot withstand a man who is determined to live. For Franz, perhaps that determination had long been extinguished. Should he have let his father’s crimes die with him or should he have brought them to the light where they were able to be struggled and contended with?

As he looked out once more into the deathly cold, he packed away the letter.

***

I still believe my letter contains some truth, it takes us closer to the truth, and therefore it may allow us to live and die with a gentler and lighter spirit.

From you loving son,

Franz

At only forty years of age, Franz Kafka passed away in 1924, his last words supposedly being “Kill me, or you are a murderer,” when he begged his doctor for an overdose of morphine. In life, there were few things he loved more dearly than his work: his little sisters and his good friend Max Brod, whom he had first met at Charles University. When Franz Kafka died, he left Max Brod a letter requesting that all of his work, his stories, and letters be burnt and destroyed. Given the enduring significance of Franz Kafka’s work today, it is clear what Max Brod’s decision was.

Chrysiallis

If Franz had any say in the actions following his death, he would have asked to be cremated, his ashes cast over a cliff face with the ocean beneath where the wind of the waves would carry his remains far and wide. He would have wished to be free like the air, liberated from the sickly and decrepit prison of his own body. But there he was, eternally trapped beneath the words:

Franz Kafka (1883 – 1924)

May his soul be bound in the union of life

Tuberculosis had condemned him to a slow and painful death. In Franz’s final weeks, Brod watched on helplessly as his friend deteriorated before his eyes. The relentless coughing ensured that the bed was perpetually stained red and the ever-growing struggle to eat could be heard in the guttural groans of every gulp. Eventually, there came the day when the suffering exceeded the need for food. His skin began to wither where there had once been flesh and the contours of his bones began to protrude like ridges. Brod thought there was nothing worse a man could face than to be tortured by his own body, knowing that the inevitable was approaching. But even in his darkest hours, Franz continued to write. Perhaps it was through writing that his spirit lived on, knowing that there was always a new day with a new pain or joy that was yet to be written.

Franz left no will. It was partly due to the fact that there was no one to whom he could leave anything to and also that he had nothing to leave to them. Brod had always thought of him as a butterfly with wings that were vibrant and radiant on one side, then dark and faded on the other. When he was around others, Franz was a man of colour, armed with an unrivalled wit and sense of humour. But when one came to learn of the man beneath the charm, they found a poor and lonely soul, full of hate and misery, wrestling with himself in an endless strife. His life had been riddled with romances and friendships, derived from temporal desire and impulse. They came and went like passing moments, taking a piece of Franz as they came and went. Brod was the only one who persisted to the very end. Their twenty-two-year-old friendship was nothing short of a miracle and sometimes, Brod himself wondered how such had come to endure. Perhaps it was their mutual love for writing. Or perhaps they saw a something within each other that they themselves did not have.

Brod had become the administrator to the estate. It was what Franz had intended and along with all of his insignificant properties, he had left a letter. As he stood at the foot of the grave, Brod reached into the pocket of his coat to reassure its safety. He didn’t need to read it to know what was written within. Surely, if Franz truly longed for his wishes to be fulfilled, Brod would have been the last person to whom he addressed the letter.

***

“You write like no one else can,” Brod exclaimed forcefully. They had met in the literature section of the German Students Club at the reading and speech hall. It was only after he had given his lecture on Schopenhauer that he was introduced to the reserved Franz Kafka. The two had struck up conversation and now formally acquainted, walked back to Ferdinand Street through the Old City of Prague. After much convincing, Franz finally ceded to Brod’s wishes to read his writing.

"My scribbling … is nothing more than my own materialisation of horror," Franz replied. "It shouldn't be printed at all. It should be burnt. It contains no literary value. I am not the genius you make me out to be and my work will never be recognised like you say it would. I write for an audience that does not exist. People do not want to hear what I have to say. They want to hear of the success, the joy, the prosperity of the world. They want to hear the triumph of man.”

“You think too shallowly of your fellow peers. It is only through the horrific and severe truth that people come to understand themselves and the world around them.”

“It takes a twisted and depressive mind to understand what I write. It takes a philosopher like Schopenhauer to perceive the phenomenal world as the product of a blind and insatiable noumenal will.”

“First you have to see the ugliness to appreciate the beauty. Your words will outlive this era and will continue to live so long as people exist. The writing surpasses the man, but it is within the writing that the man continues to live.”

"I am made of literature," Franz said, "and cannot be anything else. When I die, it is only appropriate that my writings should die with me.”

***

As per the instructions on the letter, he arrived at Franz’s apartment where he now stood in the narrow study. It was the first time since his death that Brod had returned. As he stood in the middle of the room, he could feel a certain coldness about it. One could not tell that it was once occupied, but for the chaos of ink and paper that was sprawled across the desk. The walls were bare and there wasn’t the slightest hint of a woman’s touch. It gave one the impression that whoever was the resident of this lonely coop was simply conjured into the world, existing and dissipating without anyone ever knowing, like an actor whose role is performed off-stage.

Brod manoeuvred towards the desk and sat in Franz’s chair. At a preliminary glance, the wooden chair seemed durable and smooth, but upon being seated, the frame stirred, groaning as he shifted his weight. One of the legs was also ever so slightly shorter than the others as Brod discovered, rocking from side to side just as Franz would have done whilst deep in thought. Running his fingers along the surface of the wood, he could feel deep grooves in the varnish, possibly from the continuous burrowing of fingernails.

As Brod surveyed the desk, he felt a certain guilt, like that of a child caught whilst in the act of some mischievous deed. He could feel Franz’s presence looking over his shoulder, judging his every movement as he trespassed the dead man’s belongings. With every glance of a phrase or word, written upon one of the pieces of paper, Brod felt as though he were intruding in Franz’s mind. The writer’s thoughts and ideas had been reduced to meagre scribbles, laid bare and vulnerable for all the world to see. In life, he had relentlessly guarded the contents of his mind. To Franz, his own thoughts may have seemed like a dangerous criminal from which the rest of the world needed protection. But now, with Franz gone, and his thoughts remaining, Brod removed the letter once more from within the pocket of his coat.

Dearest Max,

My last request: Everything I leave behind me... in the way of notebooks, manuscripts, letters, my own and other people’s, sketches and so on, is to be burned unread and to the last page, as well as all writings of mine or notes which either you may have or other people, from whom you are to beg them in my name. Letters which are not handed over to you should at least be faithfully burned by those who have them.

Yours,

Franz Kafka

It was a troubling dilemma. As far as the world was concerned, Franz did not exist except within these papers and the mind of Brod. His writings were sacred. They were revolutionary. They were monuments in time. It was a great violation to humanity to burn down monuments, but now the erector had asked for his palace to be torn down. However, to neglect a dead man’s wishes was the greatest breach of loyalty and faith, to defy a man when he is not even alive to fight. Surely the greatness of Franz’s work constituted one small betrayal in history.

No man wants to be forgotten. One could even say that one’s ultimate purpose in life is to ensure that he is not forgotten, yet there existed the strange mind of Franz Kafka that wished to be erased from time. Or maybe he didn’t. Maybe he just couldn’t bring himself to admit it. If he were so adamant in favour of his work’s destruction, why not burn them himself? Maybe something inside him desperately wanted to survive so that he wrote the letter to Brod, someone who would undoubtedly disregard his request.

Should he betray a friend for the world, or should he betray the world for a friend? Brod chose to do neither.